“I invented the one breath, one line method during my last year of graduate school,” says Theresa Antonellis referring to her unusual drawing process. “I wanted to find a way to synthesize everything I was thinking and learning before I started my MFA.” For many years prior, Theresa taught yoga and massage both of which involve a lot of breath work. Finding herself in the pressure cooker-environment of graduate school, she wanted to incorporate the two calming disciplines into her practice. That’s when she started experimenting with breath-generated mark making. “I was making marks based on the range of motion in my arm, and I came to settle on this very controlled one breath, one line and range of motion in the wrist or the arm plus the length of the drawing implement.“

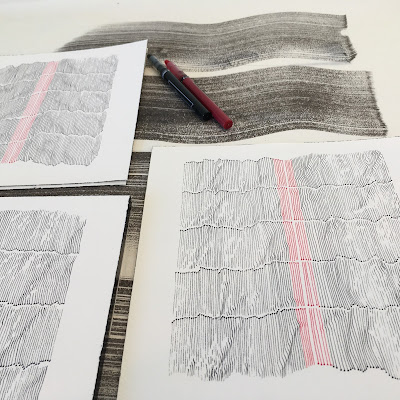

At VCCA, Theresa was working on a series of line drawings made with a ballpoint pen and larger works made with oakgall ink on Japanese paper. The work shares an affinity, but the effect is quite different.

The smaller works are tighter, more controlled. To produce them, Theresa starts at the center of the page, drawing lines from the top down. After four or five lines, she flips the image around and works in the opposite direction so that the drawing emanates from the center. Each line is made on the exhale. When she stops, she has to rest her pen to inhale and gather her focus. While she’s doing this, the ballpoint pen is resting on the page. A little puddle forms as the paper absorbs ink, creating a little dot at the end of each line. The visual embodiment of her technique, the dots tell us that’s where she paused to take her next breath. They also add a visually interesting flourish to the lines, both tempering and accenting their verticality.

Theresa has a set of rules that govern the drawings: the lines can’t touch, but they have to be as close together as possible and as straight as possible. Theresa is as interested in the resulting negative space as she is in the lines she draws. “I really enjoy that kind of white space that shows up between the lines and it becomes its own pattern. Every line is a reaction to the previous line and I feel like breath is like that. Every breath, while it may be the same length, is a reaction to the depth or the shallowness of the previous breath and the lines express that.

“During the process the pen will run into little imperfections in the paper, or my hand will express an imperfection in its range of motion and that shows up as a blip. I’ll accept that blip and I’ll continue and almost exaggerate it until it’s worked out of the image. I’ll push it out of the image much like one would massage a knot out of a muscle.“ This narrowing and widening of the space between the lines infuses the work with a rhythm and produces the effect of light and shadow.

Theresa uses the same spare language as Minimalism, but without the hermetic coolness of that genre. With the one breath, one line drawings, she has breathed soul into the work with the hand (and breath) of the artist clearly revealed.

The oakgall ink pieces involve the same approach. Because they’re bigger, instead of using just the range of motion in the wrist, she’s using the range of motion in the entire arm. “I dip the brush into the ink and make one full line on one exhale. They’re going to be as straight as possible, but there’s going to be some variation within them. And I copy that variation, so I allow that variation to be copied as I work it out.”

Made from crushed oakgalls, which are round nut-like growths that oak trees produce to protect themselves from the eggs of nonstinging wasps laid in their leaf stems. Oakgall ink dates back to the Roman Empire. In the Middle Ages, it was used in illuminated manuscripts and many of our important civic documents were written in oakgall ink.

To make the ink, boiling water is poured over crushed oakgall and left to sit over night. The next day, ferrous sulfate is added causing a chemical reaction. (In ancient times they used rust or some bit of rusty hardware.) The solution is no longer a tea; it is now a permanent dye. Initially, the ink has a midnight blue, deep purple cast, which darkens as it ages. The addition of gum Arabic emulsifies the liquid making it less watery.

Like many Fellows, Theresa feels that one of the points of a residency is to experiment, to push yourself to do something you wouldn’t normally do, so she brought a set of colored pencils with her to VCCA. Using the pencils she created a series of freehand circles in grid, selecting the colors based on a random set of rules. She wanted to represent as many colors as possible, without automatically going for her favorite colors. She also made a second grid in more neutral hues. The work is her response to the intense focus that her line drawings require. Here, she’s not really focused on the breath, but on producing a perfect circle with the gestural mark—a discipline of a different sort.

“I’m very interested in perception, this breathable boundary between what we are thinking about inside and what shows up outside. So I’m drawing these circles, which look pretty perfect to me. I haven’t measured them with a compass. But, so what is perfect? Can I draw a perfect circle? No, but I can draw a nearly perfect circle and doing this makes me feel really good. I like the idea of drawing something that is physically in me and expressing that outwardly. And then there’s the idea of what does it take to perceive something? Some of these are barely coming off the page and others are much more delineated, much more detailed. I like the idea of the eye falling on the image and the moment it begins to see the image emerging from the page.”

When not working on her art, Theresa teaches art history at Slippery Rock University, Pennsylvania where she also runs the Martha Gault Art Gallery.